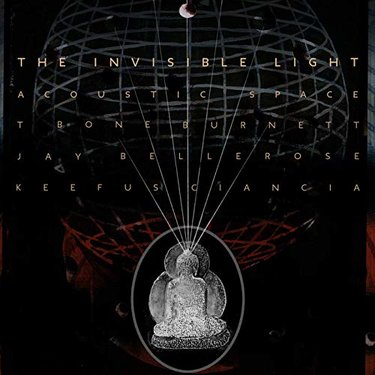

T Bone Burnett’s Invisible Light: Acoustic Space

Two strong early contenders for “best album” of 2019 dropped in the last couple of weeks. In many ways they could not be more different from each other. Sara Barreilles’ Amidst The Chaos is a study in mainstream pop perfection, clearly honed by the artist’s Broadway success but true to her troubadour roots, while T Bone Burnett’s dystopian The Invisible Light: Acoustic Space is a twisted experiment of dark poetry set to deconstructed European folk music run through an electronic / industrial blender. Barreilles uses perfectly crafted melodies and lyrical precision to explore the power of self-respect and the nature of love – with the damage done to the image of God in each of us by the chaos we allow to run amok in our hearts as a subtle subtext – and then sings those songs like some kind of angel. Burnett, on the other hand, along with percussionist Jay Bellerose and ambient keyboard electronicist Keefus Ciania, (both of whom he has worked with for years on the soundtrack for the HBO series True Detective,) has concocted pieces that sound like audio postcards from somewhere just outside the gates of Hell.

Two strong early contenders for “best album” of 2019 dropped in the last couple of weeks. In many ways they could not be more different from each other. Sara Barreilles’ Amidst The Chaos is a study in mainstream pop perfection, clearly honed by the artist’s Broadway success but true to her troubadour roots, while T Bone Burnett’s dystopian The Invisible Light: Acoustic Space is a twisted experiment of dark poetry set to deconstructed European folk music run through an electronic / industrial blender. Barreilles uses perfectly crafted melodies and lyrical precision to explore the power of self-respect and the nature of love – with the damage done to the image of God in each of us by the chaos we allow to run amok in our hearts as a subtle subtext – and then sings those songs like some kind of angel. Burnett, on the other hand, along with percussionist Jay Bellerose and ambient keyboard electronicist Keefus Ciania, (both of whom he has worked with for years on the soundtrack for the HBO series True Detective,) has concocted pieces that sound like audio postcards from somewhere just outside the gates of Hell.

Each project is brilliant in its own right, for similar and completely different reasons. I suppose I should not have been surprised – especially as someone who has been studying and appreciating his work since I was 12-years-old – to find out that T Bone Burnett produced them both.

Burnett, though always in demand behind the scenes, has been frustratingly stingy as an artist in his own right. Depending on how you count, his most recent solo outing was nearly ten years ago. I suppose being as in-demand as Burnett has been as a producer (Allison Krauss and Robert Plant, Gillian Welch, Elton John and Leon Russell, Gregg Allman, Grace Potter and the Nocturnals,) and as a soundtrack producer or music supervisor for films and television series (O Brother, Where Art Thou?, The Big Lebowski, Walk The Line, Crazy Heart, Inside Llewyn Davis, Nashville,) and as the head of his own boutique label and production company, keeps a guy busy, but it seems he genuinely prefers the supporting role to the performer’s spotlight. His recent role as a keynote speaker at the influential South By Southwest Conference, which should be required viewing, or reading, for all tech enthusiasts, aspiring artists, and students of human culture and history, reveals Burnett’s expansive understanding of human nature, communication, philosophy, and political theory. He brings all of this – his sense of the ancient and the modern, science and philosophy, God and the devil – to his art.

According to press materials and several interviews, this year’s three-part release, of which The Invisible Light: Acoustic Space is the first part, will wrap up his recording career. Though, at 71 years of age, and with the awards, success, and more importantly, impact, that he has had, he is certainly entitled to do whatever he wants, I don’t like the sound of that. There is simply no artist out there that does what T Bone Burnett does.

This project is connected to an epic poem he has been composing for several years. That source material provides a rich base from which these dreams and nightmares spring. And, as has long been the case with Burnett, the subject centers around human nature, our propensity for self-harm, and where the fractured light that dapples the walls of our caverns may be coming from. The “Invisible Light” part of title is borrowed from a play / poem composed by T.S. Eliot in 1934 called Choruses from The Rock. Songwriters and artists should take a few minutes to read Eliot’s work, both as an inspiration in and of itself, and as an example of the immutable truth that the greatest artists out there are constantly absorbing other great art. Eliot’s poem, though written about England in the 30s, is shockingly applicable to Evangelical America today. His challenging image of God as an “invisible Light” is rich with implication, and the idea that darkness reminds us of that Light, is central to understanding not only the nature of the externalized evil we see rising in the world around us, but the insidious shadows that work to crowd out the little lights in our own hearts.

As I have said many times, the very inklings of the thoughts that became True Tunes were strongly informed by an interview I read with Burnett when I was about 12-years-old. By then, Burnett, in his early 30’s, had already been in several ground-breaking bands, including The Alpha Band with Steven Soles and David Mansfield (who released three new-wave albums for the Arista label.) He (and the other members of that group) backed up Bob Dylan for his legendary Rolling Thunder Revue tour and were with him just before his “born-again” phase.

Though he considered himself a believer, (he came from an Episcopalian background, but his grandfather was a Secretary of the Southern Baptist Convention,) and often dealt with spiritual issues in his music, when Burnett emerged in the 80s as a solo artist it was never in the increasingly commercially viable “Christian Market.” Although he bumped up against that space, producing records for artists like Leslie (Sam) Phillips and Maria Muldaur and helping with the creative direction of What? Records, (a very hip division of Myrrh / Word,) Burnett was an example of an artist of faith insisting on working in the “real world.” In that 1982 interview I read that he believed that as a follower of Jesus he could either write songs “about the light” or he could write songs about “what he sees because of that light.” He chose the latter. Almost four decades on it seems he has chosen to sing about the light, albeit in a pretty dark way.

T Bone’s faith has given him a perspective that is definitely at odds with the prevailing Evangelical mainstream in America. We’ve heard it throughout his career, and this collection is no exception. In fact, as dark as this album may seem, it is also arguably among his most clearly theological work. The set opens with a chant, singing “Love makes me stammer when I talk / Love makes me stagger when I walk” before his narrator voice kicks in speaking a series of lines full of Biblical and apocalyptic images. We get the idea that the “love” in question here is the 1 Corinthians 13 kind. The tone is set and we know we are in for more of a musical shadow play than a straight-ahead rock record.

The theme continues, and deepens. “A Man Without A Country (All Data Are Compromised)” riffs on Philippians 3:20 along with a litany of things the singer thought we as a species would have figured out by now, before seeming to realize that our redemption comes from somewhere else. Images of “machines of love and grace” and “dying by binary code” create a wonderfully cryptic blend of “Blade Runner,” “The Matrix,” C.S. Lewis’ “The Great Divorce” and the book of Revelation.

“To Beat The Devil” is actually pretty straightforward advice, though it sounds like it’s coming from someone who smells like sulfur. It’s almost as if Uncle Screwtape joined the Beat Generation. “Anti-Cyclone” does a brilliant bit of trickery by sounding the most like an actual song at first, before completely decomposing into a piece of concept art, then re-shaping itself again. Distorted accordions, strange percussive sounds, and a wonderful sense of ambience, give the proceedings a romantically creepy, clown-like tone that fits the lyric perfectly. “If you tell people things they already believe, they will believe you. It doesn’t matter that you don’t believe a word you say. And as the deal goes down the world outside will tremble, and disassemble. For the ventriloquists who look the other way this is a good day.”

The characters at the center of “The Secret In Their Eyes,” who have clearly sold their souls long ago, have come to the end of their roads and have nowhere to look but up. “Being There,” though, is probably the Rosetta Stone of the set. If there is an answer to the madness, a way out of the hall of mirrors, it seems wrapped up in the simple instructions “Be not afraid, be not afraid, the angel bade.” Being present, not tuned out, and being awake and unafraid; that’s the secret to cutting the puppet masters’ strings. Burnett takes us into a nightmare in order to expose it from the inside.

The real win, here, is that instead of taking pot-shots at easy targets, Burnett sets his poetic sites on the deeper philosophical and theological drivers of the human mess we see being lived out in front of us. Though it’s clear that our madness has political implications, for instance, this is not a political project. It’s a spiritual one.

Though long-time fans won’t be thrown by the largely spoken-word nature of the set, newcomers may find it a bit challenging to engage with at first. Be assured, your efforts will be rewarded. On the other side of this sonic forest is a provocative, soulful, and even strangely optimistic appraisal of the state of mankind in these bleak days. In revealing interviews with The New York Times and The Los Angeles Times Burnett reveals several of his literary influences and tips his hand a bit about the forthcoming installments in this series. The second set, he says, will be more rock and punk oriented, while the third will be “very very jazz, pretty out there.”

He’s got my attention!