Jesus Music Rediscovered?

Multiple Films and an Unlikely Roots Gospel Album Bring Back Old Sounds and Raise New Questions About The Roots, Range, and Future of ‘Jesus Music’

Multiple Films and an Unlikely Roots Gospel Album Bring Back Old Sounds and Raise New Questions About The Roots, Range, and Future of ‘Jesus Music’

A Reflection by John J. Thompson

With the upcoming release of the Lionsgate film “The Jesus Music,” (Oct 1) for which I served as an interview subject and historian, as well as the fictional romantic comedy “Electric Jesus” (1091 Pictures, Nov 2,) about an imagined Christian hair metal band in 1986, (for which I served as Music Supervisor and as a special historical consultant,) there has been a lot of talk lately about the roots of contemporary Christian and Gospel music and the spiritual revival that literally rocked parts of the world fifty years ago. Many have asked me what, “as an expert,” my opinion is of these projects and if I think the Christian music industry’s tilt toward “worship music” may represent a return to its roots in the halcyon Jesus Movement days of the late 60s and early 70s. My short answer to the first question is that I hope millions flock to see both movies and then engage in thoughtful and spirited discussions about them. My short answer to the second question is, unfortunately, no. The 21st Century, Evangelical Industrial Complex bears almost no resemblance to the diverse, disparate, desperate sound of a generation finding hope in a reimagined, counter-cultural Deliverer. To my eyes, these films, and other recent releases, reveal exactly that.

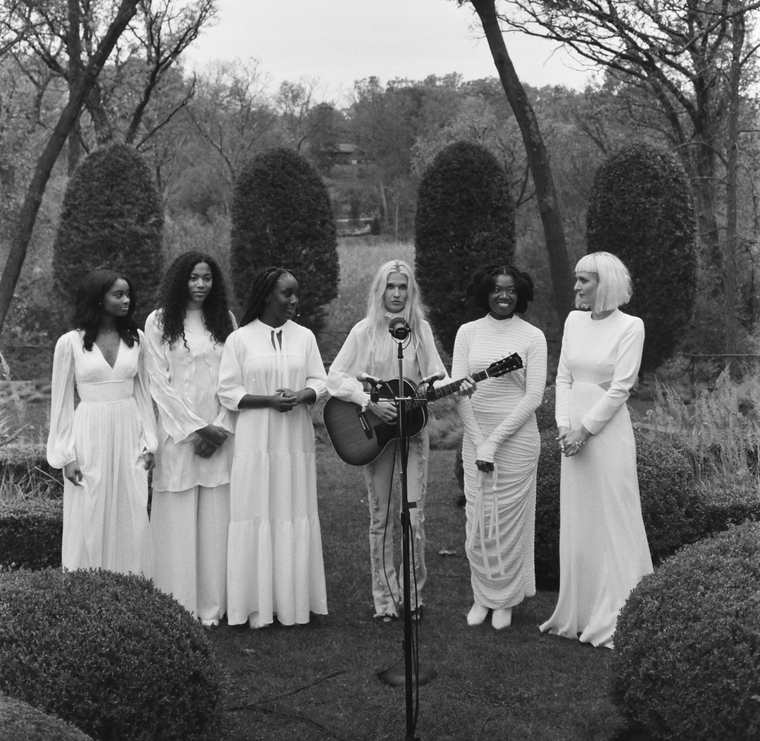

The debut solo album by Natalie Bergman, for instance, absolutely does offer a call back to the roots of “Jesus Music.” Mercy, released earlier this year on Jack White’s Third Man Records, blends elements of West African world music, 60s Motown Soul, psychedelia-tinged Gospel blues, and mercurial folk as a backdrop for Bergman’s mournful yet lovely lyrics. Though songs like “He Will Lift You Up Higher,” “Shine Your Light on Me,” and “Talk To the Lord,” all spring from a place of pain and loss after a shocking death in her family, they are as obviously and unselfconsciously devotional as any of the early tunes by Larry Norman, Honeytree, or Love Song. In fact, I suspect it is precisely because of Bergman’s posture as a person in need, hands and heart open, and with no awareness of or compulsion to cater to market pressures, labels, or expectations in the faith-based economy, that she has been able to craft an album that is so inviting, innovative, and effective. It’s fascinating to me that this year, with two films delving into the roots of Christian rock and pop, it is a mainstream artist with no awareness of the evangelical subculture who has dropped the most compelling Roots Gospel, true “Jesus Music” album of the last several years, if not decades. One hopes it might inspire other young artists to re-calibrate their concepts of what Jesus Music can, and even should, be in troubled times.

The debut solo album by Natalie Bergman, for instance, absolutely does offer a call back to the roots of “Jesus Music.” Mercy, released earlier this year on Jack White’s Third Man Records, blends elements of West African world music, 60s Motown Soul, psychedelia-tinged Gospel blues, and mercurial folk as a backdrop for Bergman’s mournful yet lovely lyrics. Though songs like “He Will Lift You Up Higher,” “Shine Your Light on Me,” and “Talk To the Lord,” all spring from a place of pain and loss after a shocking death in her family, they are as obviously and unselfconsciously devotional as any of the early tunes by Larry Norman, Honeytree, or Love Song. In fact, I suspect it is precisely because of Bergman’s posture as a person in need, hands and heart open, and with no awareness of or compulsion to cater to market pressures, labels, or expectations in the faith-based economy, that she has been able to craft an album that is so inviting, innovative, and effective. It’s fascinating to me that this year, with two films delving into the roots of Christian rock and pop, it is a mainstream artist with no awareness of the evangelical subculture who has dropped the most compelling Roots Gospel, true “Jesus Music” album of the last several years, if not decades. One hopes it might inspire other young artists to re-calibrate their concepts of what Jesus Music can, and even should, be in troubled times.

The Movement

Amir “Questlove” Thompson’s stunning documentary “Summer of Soul” (Hulu) inadvertently touches on the Jesus Movement era as well. It places hardcore Gospel artists (Mahalia Jackson, The Gospel Redeemers,) alongside “crossover” groups like The Edwin Hawkins Singers (with their smash hit “Oh Happy Day”) and the Staples Singers’ blistering blend of blues, Gospel, and rock, right up there with Sly and the Family Stone, Stevie Wonder, B.B. King, and many others. It’s a fascinating comparison. “Summer of Soul,” covers the long-overlooked 1969 Harlem Cultural Festival which brought a diverse collection of Black and Brown artists to Mount Morris Park in the heart of one of the communities that had been most devastated after the assassination of The Rev Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.. The film is a veritable meditation on cultural engagement. The audience was presented with everything from escapist entertainment to intentionally provocative message music. There were pastors and Panthers – and the listeners would have to decide who to follow. There was also a much broader selection of music than even the Harlem natives expected, and some pithy juxtapositions of wider cultural moments. Sure, the U.S. made her moon landing that same summer. Not everyone in Harlem was impressed.

Mavis Staples (L) and Mahalia Jackson perform at the Harlem Cultural Festival, as documented

in Summer Of Soul (PHOTO COURTESY OF SEARCHLIGHT PICTURES. © 2021 20TH CENTURY STUDIOS

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED)

Due to some combination of licensing problems, administrative malfeasance, and general lack of interest, the footage of the Harlem Cultural Festival languished for decades as memories of the massive event faded. The Woodstock festival, however, which happened just a few hours away and drew mostly white teens and young adults, has been obsessed over as a watershed moment in American popular culture ever since it happened. This contrast presents an interesting example of the power of history, story, and branding, and asks some powerful questions about who, exactly, is writing that history.

“The Jesus Music,” on the other hand, traces the roots of modern Contemporary Christian Music (CCM) back to certain corners of the movement that impacted millions of people at that same time. Rocked by their own anger and confusion over the Vietnam war, and laden with frustration with their own parents and elders resisting the Civil Rights movement, throngs made up largely of teens and college-aged young adults embraced that long-haired, sandal-wearing, peacenik Jesus. Hundreds of thousands were baptized in the ocean off the coast of Southern California. Rock bands traveled in funky old buses playing free concerts in parks and singing testimonial songs about how Jesus had blown their minds. Christian hippies strummed their acoustic guitars and sang protest songs loaded with scripture.

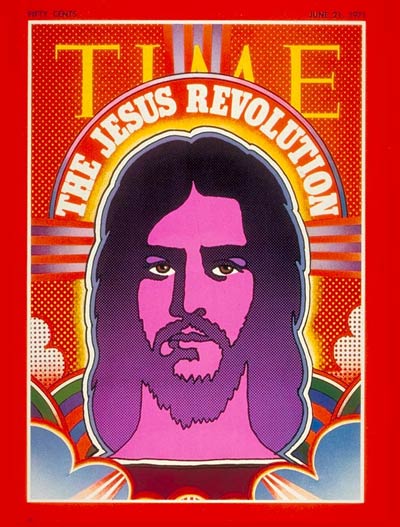

They say history is written by the victors, and the way Evangelicals talk about the Jesus Movement is one excellent example of that truism at work. As polished and engaging as “The Jesus Music” film is, and I’m happy to have contributed to it, by cutting it down from its proposed episodic format to under 2 hours, the producers were forced to craft it into more of an origin story for CCM, with a handful of representative artists standing in for many others, rather than a comprehensive history of all facets of the Jesus Movement and its musical manifestations. There were many streams, for instance, that flowed into the “Jesus Revolution” that made the cover of TIME Magazine. The film makes no mention of the reforms instituted in the Catholic Church at Vatican II that allowed the Mass to be performed in the local language instead of Latin and allowed contemporary music to be used in church. Folk services flourished as priests, nuns, and monks engaged in the same social struggles and questions that many Catholic youths were confronting. The Jesus Movement was not nearly as monolithic, nor as Protestant/Evangelical/Fundamentalist as it is often presented and eventually became. Though this film does not tell the full story of the movement, or of the Jesus Music that came from the “secular” world, or of the Catholic or mainline Protestant streams of the church during that time, it does accurately follow its own family tree back to a point.

They say history is written by the victors, and the way Evangelicals talk about the Jesus Movement is one excellent example of that truism at work. As polished and engaging as “The Jesus Music” film is, and I’m happy to have contributed to it, by cutting it down from its proposed episodic format to under 2 hours, the producers were forced to craft it into more of an origin story for CCM, with a handful of representative artists standing in for many others, rather than a comprehensive history of all facets of the Jesus Movement and its musical manifestations. There were many streams, for instance, that flowed into the “Jesus Revolution” that made the cover of TIME Magazine. The film makes no mention of the reforms instituted in the Catholic Church at Vatican II that allowed the Mass to be performed in the local language instead of Latin and allowed contemporary music to be used in church. Folk services flourished as priests, nuns, and monks engaged in the same social struggles and questions that many Catholic youths were confronting. The Jesus Movement was not nearly as monolithic, nor as Protestant/Evangelical/Fundamentalist as it is often presented and eventually became. Though this film does not tell the full story of the movement, or of the Jesus Music that came from the “secular” world, or of the Catholic or mainline Protestant streams of the church during that time, it does accurately follow its own family tree back to a point.

Jesus: The Rock Star

Jesus was everywhere in the early 70s. Webber and Rice topped the charts with “Jesus Christ Superstar,” a skeptical rock opera (to be generous) while the kinder, gentler “Godspell” had its own batch of supporters and detractors. Just as more “mainstream” religious agents have done all along, elements of the counterculture co-opted the Son of Man long before Calvary Chapel tapped a long-haired preacher named Lonnie Frisbee to reach out to hippie kids in Orange County. The Beatles, Bob Dylan, even the Rolling Stones had been stoking those coals for years. Cults took advantage of the spirit in the air as well, and from Broadway and the Top of the Pops to Hollywood’s Skid Row, Jesus was having a major moment. The lines around the movement are not nearly as tidy or straight as proponents of its megachurch progeny might have us believe. But alas, complicated stories are hard to capture in short montages. For an alternative perspective on the Jesus Movement, don’t miss the stunning Apple TV docuseries, “1971: The Year That Music Changed Everything.” Its inclusion of the strung-out Rolling Stones singing about wanting to see Jesus’ face on Episode 2 makes a nice counterpoint to the CCM version of “The Jesus Music.” The Erwin Brothers’ inclusion of Resurrection Band’s Glenn Kaiser is also a critical link, and one rare example of the spirit of the counterculture that has survived to today.

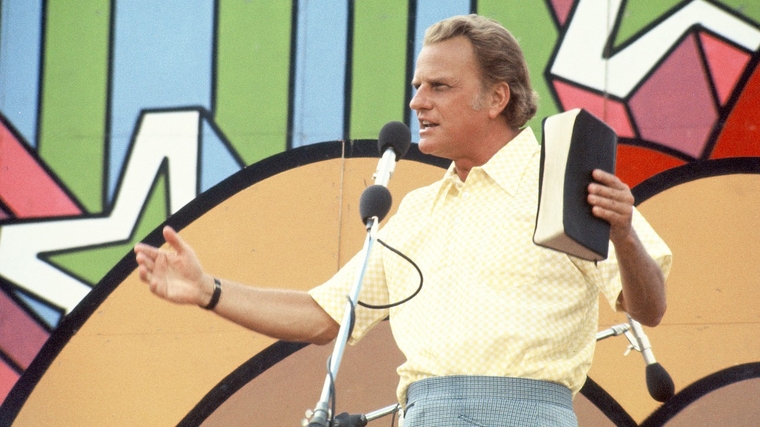

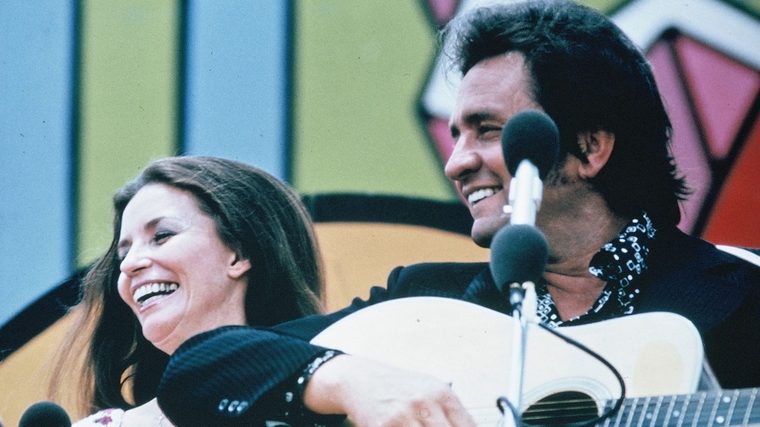

In 1972, just 3 years after both the Harlem Cultural Festival, Woodstock, and the disastrous Stones show at the Altamont Speedway at which four people died, over 200,000 Christian college students gathered in Dallas for “Explo ’72,” to hear music by Larry Norman, Kris Kristofferson, contemporary Gospel pioneer Andrae Crouch, and even Johnny Cash. They also heard from the evangelist Billy Graham. Although later known as a somewhat apolitical spiritual guide to presidents of either party, In 1972 Graham worked closely with Nixon – including giving him specific advice on how to engage Christian audiences to secure re-election. Although the festival’s organizer, Bill Bright, ultimately refused to provide Nixon with a platform, Graham had personally pitched Nixon the idea of coming – promising that he could reach young potential voters, minorities, and wealthy Texans. (You can hear the conversation yourself HERE. Scroll down to Conversation 662-004 and to the 16:00 mark.) Nixon was sold. He wanted to directly address the crowd in Dallas but had to settle for having a delegate read his message on his behalf. His simultaneous words of support for the continuation of the Vietnam war and for living a life based on spiritual values were very well received by most of those gathered to rock for Jesus. A small cadre of anti-war students was shouted down by the larger crowd. None of this political chicanery, which by most accounts was not a defining feature of the festival, is covered in “The Jesus Music,” though the film does include some inspiring words from Graham about cultural engagement with the challenges of the day. To be fair, though, as much a student of Explo as I have been for decades, I never heard about this until recently. A couple of friends, who were there, confirmed these memories after I read about them in “Jesus and John Wayne” by Kristin Kobes Du Mez. Years later it would come to light that it was actually during the very week of “Explo ’72” Nixon’s operatives were breaking into the Watergate Hotel.

“The Jesus Music” correctly locates the genesis of CCM in this movement, maybe even, for better or worse, at “Explo ’72” itself. It also documents Graham’s endorsement of contemporary music as a key component of the genre’s eventual success with the mainstream Evangelical world. It even hints, ever so delicately, that “Explo ’72” may likely have represented the end of the Jesus Music era, and possibly the Jesus Movement itself, even as an industry was being born. Was that massive Evangelical festival the Jesus Movement’s spiritual Altamont?

Sister Rosetta Tharp circa 1938

The Music

When the “father of Christian rock,” Larry Norman, said that Rock and Roll was not the devil’s music, but had originally belonged to the church – and that he was just “stealing it back” – was he thinking in generalities, or about Sister Rosetta Tharpe, the African American electric guitar innovator who is now widely recognized as a true trailblazer in Gospel, Blues, and Rock and Roll? Or maybe the White Gospel music of the American South that found expressions in flashy quartets, humble mountain music, and Pentecostal church services. Either way, he was right. When you trace the origins of Gospel, Contemporary Christian Music, Country, and Rock and Roll – it all finds common parentage in the struggle, tension, and groove of what we now call Roots Gospel.

Gospel music has taken many forms over the last several centuries. Quartets, sacred steel, Appalachian folk, sacred harp, and even the old field hollers brought to the New World by slaves were all used for spiritual, emotional, and social support as men, women, and children worked to build wealth for their masters. Even the relatively modern form, developed and popularized by the likes of Thomas A. Dorsey, Albertina Walker, James Cleveland, and Mahalia Jackson is clearly anchored in sounds that came before. Dorsey, in fact, one of the most prolific and gifted Jazz and Blues artists of his day, saw no distinction between those genres and Gospel. Of the 3,000 songs he penned, a third were Gospel tunes, including “Take My Hand, Precious Lord,” and “Peace in The Valley.” If “The Jesus Music” had traced its roots back just a bit farther than Larry Norman, they would have found Dorsey, Sister Rosetta, and the sound of struggle and hope. Though she doesn’t appear in their film either, “Electric Jesus” has played Sister Rosetta’s music before every screening and film festival appearance over the last year.

Bergman’s New Expression of Jesus Music

Natalie Bergman grew up in a casual, non-denominational Christian home. Her main exposure to sacred music was singing hymns at church and singing in a Gospel choir at school. She has realized significant success in the mainstream alternative pop world with the rock band Wild Belle, formed with her brother Elliot. Wild Belle earned strong reviews and a loyal following for their genre-bending sound, compelling live shows at places like Lollapalooza, Coachella, and South by Southwest, and lyrics that celebrated the wilder side of sexuality and party life.

That all changed when the siblings’ father and stepmother were killed by a drunk driver in 2019. Having lost their mother several years earlier, this sudden orphaning was devastating. In a recent conversation with the True Tunes Podcast Bergman explained the way this profound loss brought her into the darkest dark and the brightest light she had ever experienced. “I felt like I had lost my identity,” she said, “I didn’t know who I was as an artist or a musician anymore and I really didn’t think I could get back to music.”

Bergman eventually made her way to a monastery and retreat center in New Mexico, hoping to find some solace in a spiritual place. “I read a lot,” she recalls. “I referenced the Bible, and I listened to monks chant seven times a day. I spent seven days in silence. I listened and I received some powerful spiritual answers.”

She goes on to explain that once she began to experience the healing she sought, music found her again. She came to the relatively surprising realization that she had a Gospel record to make. “These songs found me, and they needed me to write them. I found that writing this album was a very healing process and through it I found hope. That is what I aim to inspire in those who listen to it.” She not only wrote all the songs but played the instruments and recorded the project herself – in her brother’s home studio. After it was finished, a copy landed at Third Man Records, and they immediately heard a potential partnership.

Like the performers of the earliest Jesus Music, and the even earlier expressions of Roots Gospel, Natalie Bergman, having found peace in the midst of a storm and healing in the midst of pain, sought to offer uplifting hope, more than self-serving complaints or high-minded advice through her songs. “I was listening to this Johnny Cash song called ‘It Was Jesus,’ every morning,” she recalls. “It’s a very hopeful, uplifting song. It occurred to me that music allows for those hopeful, feelings. I was listening to these up-tempo, joyful Johnny Cash tunes and he’s singing about Jesus and I’m like – wait a minute – I want to sing about Jesus!”

Bergman does a lot of that on Mercy – somehow managing to craft songs like “I Will Praise You” and “Shine Your Light on Me” that are both playful and melancholy at the same time. “I wanted to write these kind of wake-up anthems,” she explains. “The same way ‘This Little Light of Mine’ gets in you and puts a little pep in your step. I wanted to create some joyfulness around the music.” That spirit of sober-minded joyfulness was something Johnny Cash was well known for, and it was not lost on Bergman. “You didn’t have to be a believer to love his music,” she added. “That’s what I want this music to do. I think it can speak to all varieties of people; religious or non-religious.”

And although Bergman did not grow up listening to Christian music and was not familiar with the Jesus Music that pre-dated modern CCM, after sitting through a brief primer during the recording of the podcast she resonated with its ethic immediately. “This is very exciting to me,” she enthused. “I’m making Jesus Music. I’m a part of that!”

“The Jesus Music” film is a very well-made and engaging introduction to the lineage and ancestry of modern worship and CCM music. It may not tell the whole story of the Jesus Movement, and it doesn’t even touch on Christian artists such as B.J. Thomas, U2, T Bone Burnett, or 21 Pilots who decided against making music specifically for Christian audiences. But what it does it does well. The producers have hundreds of hours of interviews waiting to be organized, edited, and released. Hopefully, this film will act as a sort of opening salvo of ongoing exploration. By focusing on representative figures; Amy Grant, Michael W. Smith, Toby Mac, Kirk Franklin, and Stryper’s Michael Sweet, they are able to establish what CCM is, where it comes from, and in the case of Franklin and the genre’s lingering whiteness, where it still has some blind spots worth addressing.

“Electric Jesus,” with which I was much more personally involved, offers a more humorous and critical, though loving, lens through which to reflect upon the bombast of Christian Rock in particular, and the entire Evangelical subculture in general. It gently asks some questions about the underlying agendas (“to make Jesus famous,”) even as it hints at what the whole thing was supposed to be all about. Did some of us lose the proverbial baby in the bathwater as we jettisoned our Spandex pants, questionable theology, or misguided hairstyles? Though a product of writer/director Chris White’s imagination, I hope that the world of “Electric Jesus,” and the complicated questions it raises, ring true – because as a historical consultant, helping to establish that was part of my job.

And while many of us are enjoying the great synergy of these two films coming out so close to each other, with the other great offerings on the air this Summer contributing to the conversation about the history of Christian music and a cultural movement a half-century ago, what gives me great hope is that Natalie Bergman is in a club somewhere, allowing God to transform her pain and loss into empathic and worshipful art to which everyone can sing along.

Click HERE to hear my conversation with Andy Erwin and Chris White, on the True Tunes Podcast, along with a survey of “Jesus On The Mainline” (a look at songs that tackled faith, God, and Jesus outside of the Christian music industry.)

Click HERE to hear our complete conversation with Natalie Bergman, along with a deep dive into pre-Explo ‘72

Click HERE to hear our conversation with the writer and director of “Electric Jesus” (Chris White) including a special conversation with Brian Baumgartner (Kevin, from “The Office”)

Click HERE to hear our conversation with the late Jesus Music pioneer, LARRY NORMAN