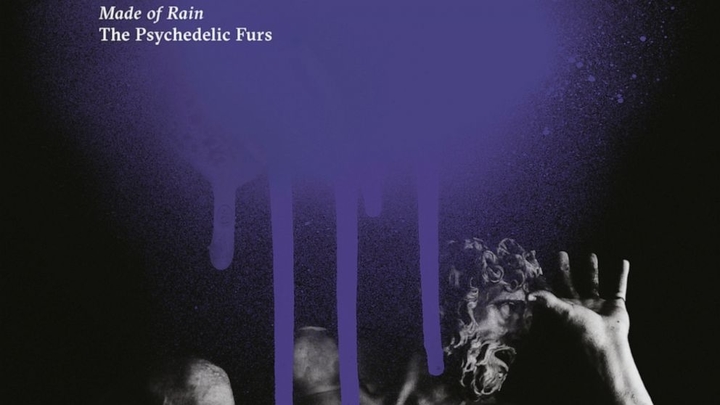

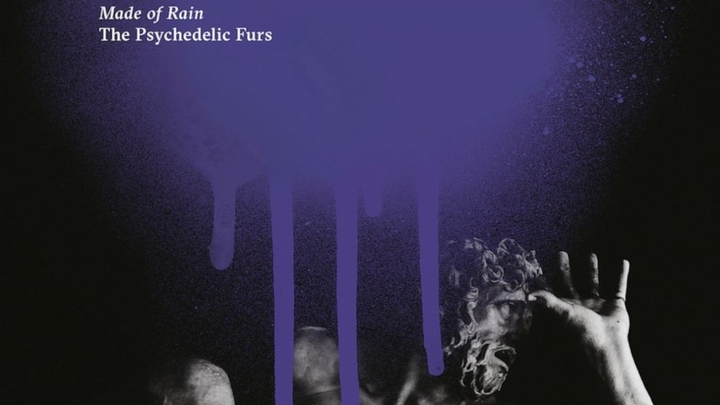

The Psychedelic Furs’ Rock and Roll Eschaton

Psychedelic Furs – Made of Rain

It’s been 29 years since The Psychedelic Furs released a completely new album. It’s probably been longer than that since an alternative band made a “reunion” project this late in the game that rivaled any of their earlier work. The Furs offered a fascinating and, at times, mystifying blend of sardonic wit, romance, despair, and proto-emo 80s excess that shimmered enough to blast up the charts and churned enough to stir the goth kids. It was hard to tell what it was about, though. By the time alternative music became mainstream, The Furs were ready to call it a day. Although lyricist and vocalist Richard Butler and his brother and bassist Tim continued on a smaller scale with Love Spit Love, and The Furs reunited for a tour around 20 years ago, new music never materialized until now – just when we need it.

To be sure, a few good hooks, some vaguely singable lyrics, a few soaring sax lines, and that wall of pulsing sound would have been enough to punch our cards. In a non-pandemic year, the band could undoubtedly have mounted a hugely successful tour and would have easily landed some commercial placements and some spins on radio. All we X-ers really want is a bit of John Hughes era nostalgia, right? Instead, we are treated to a meticulously crafted piece of work that is as emotionally and spiritually complex as it is musically dense.

Butler has long had a penchant for using religious iconography in the service of pop. But where “Imitation of Christ,” from their 1980 debut used the messianic metaphor as a stand-in for any kind of suffering, and “Heaven,” from 1984’s Mirror Moves seemed to be an oblique reference to the difference between whatever the spiritual reality of love as compared to the political or commercial machinations, the material on Made Of Rain digs much deeper than mere metaphor. Inspired by a book-length poem entitled The Man Made of Rain by Irish poet and author Brendan Kennelly, Butler has crafted a profoundly introspective and reflective set of songs that, while not quite coming off as a concept album, holds together nearly as well as one both sonically and spiritually.

The journey opens with “The Boy That Invented Rock & Roll,” a confessional paean that wreaks of Ecclesiastical ennui. Butler rolls through his unassailable resume as a bona fide rock star as the band crafts a luscious curtain of sound for him to slither in front of. The track is loaded to the brim with old-school rock wonder; produced masterfully by former Love Spit Love member Richard Fortus, (who has also been a member of Guns N’ Roses, Thin Lizzy, and several other bands.) Within seconds it is clear that this is a record made by people who remember how “epic” is supposed to sound. As Butler reminds the listener of his pedigree, and just how valuable he feels it is (spoiler alert: not very,) saxophonist Mars Williams spins his golden tone, while drummer Paul Garisto and Tim Butler lay down the rhythmic foundation for new members Rich Good (guitars) and Amanda Kramer (keys and backing vocals) to layer upon. Fortus, recording in his home town of St. Louis, Missouri, pulls all of the parts together with absolute precision. Despite the sonic density, he makes aural space for the constant stream of new sounds. Beyond merely showing the kids how it’s done, however, this attention to detail right out of the gate creates a level of gravitas that undergirds the entire project. It is clear from the get-go that this is a band that knows what they are doing and have gone to great lengths to do it well. And after telling us, tongue bloodied and in cheek, that he invented rock and roll, Butler begins his elaborate album-length poem that seems to be much more intentional, meaningful, and ultimately hopeful than anything he has written to date. Before we get to the relatively happy ending, though, Butler has some stuff to burn down.

“Don’t Believe,” which was the first single for the project, does a wonderfully tricky, circular thing with the lyric, and Butler does nothing to answer the question “where does the punctuation go?” The cleverness is the chorus: “I don’t believe – I don’t believe you don’t believe me I don’t believe you – don’t believe it’s true.” Is he saying he doesn’t believe, or that he doesn’t believe that you don’t believe? The verses repeat grievances about the state of the world; that “Money’s got the medicine,” and “you can’t believe in anything.” Then there’s “Life is short and God is gold / Promises are bought and sold / And everything I never said / Comes crashing on my tiny head.” Later he adds, “Nothing down here’s ever free / The same sun shines on you and me,” a seeming reference to Jesus’ words in the Sermon on the Mount where, in Matthew 5, after telling his audience to love their enemies and pray for those who persecute them, he says, “For he causes his sun to rise on the evil and the good, and sends rain on the righteous and the unrighteous.” Right out of the gate, Butler seems to be saying that there are a good many things we should not trust and in which we should not believe. But maybe there is also a hand at work here.

“You’ll Be Mine” feels downright eschatological when taken in this overall context. “When the new black is white / and the new low’s a high / like the ticking of the time / You’ll be mine.” There’s a promise here, but when will it be realized? “Don’t be surprised,” he keeps singing, as if this change will come on suddenly and unexpectedly. Like a thief, maybe?

“Wrong Train” sounds like a mash-up of Job, the prodigal son, and Lamentations, albeit with quite a bit more humor. The protagonist finds himself empty, living a hollow life, and looking for something more. It’s followed by – and even shares a musical interval with the first slow song on the set. “This’ll Never Be Like Love” is a moment of realization and mourning. “A cold and drowning sea of secrets that you keep / The hand that moves the time, the tears -well never mind.”

The mournful lilt continues into the next track, a beautiful lullaby of a song called “Ash Wednesday” that wearily contemplates a party on the morning after, again wondering if a celebration is in order, or mourning. “Ghosts of shadows / That you’ve become / It might be broken / And love lies murdered / The devil’s footsteps / upon the stairs.” But the closing chorus is just devastating. “So close your crazy eyes / And sing yourself to sleep / And shut your crazy mouth / Your words don’t mean a thing.”

And then the second half of the album opens with a bang. “Come All Ye Faithful” pulses and grooves with Near-Eastern horn lines, and a brutal, cavernous groove. Butler struts through the proceedings with a lyric that is a kissing cousin to “Sympathy For The Devil” and should serve as a rebuke to the pious who have allowed a snake to slither into their sanctuary and take over. On its heels, “No One” comes careening, with more warnings about the fruit that comes from bad choices. It’s a gorgeously sad song about what happens, ultimately, to the folks that failed to sober up to the seductions of the tempter in the previous song. “Tiny Hands,” a sort of demented child’s ballad, is yet another thinly veiled indictment about men, or likely one man in particular, who allowed childhood immaturity and insecurity to turn into something far more sinister in adulthood.

“Turn Your Back On Me” repeats one idea over and over throughout its lovely, droning, mid-tempo ride. “We keep coming back / We keep coming back / To this dirty town / We keep coming back.” Is this the lament of a serial repenter? Is this a dog returning to his vomit?

The album closes with “Stars,” a track that starts all clean and pretty – almost too pretty – but with lyrics that, once again, suggest something deeper. “The stars are out, they spark and flash,” Butler begins, with gentle, lovely keyboards and crystal clear guitars chiming, before adding “a snake is sliding through the grass underneath.” The chorus simply says, “These are the days that we will all remember,” before the energy level amps up considerably. This picture of days, either present or to come, where both beauty and danger exist concurrently, builds into a blistering, towering, massive wall of music. It’s an entirely different energy at the end of the song than it was at the beginning. The sound – borderline cacophony by the time it cuts out – is like an orchestra of electronic and organic noise, a rock and roll eschaton.

It’s possible that Butler intended none of this. As common as a single song, or even a couple of songs with vaguely spiritual overtones might be, however, a full project with this level of theological potential – especially from this band – seems exceedingly unlikely. That’s the fun part about art, though. One listener can hear this album as an intentionally evocative spiritual journey into contemplation, repentance, discernment, and even worship, while others may not. The strength of the work, however, is undeniable. This is definitely a vinyl-worthy investment.